Ashila Dandeniya: Fair worker treatment for fair fashion

My first job was in the garment sector was in 2001 as a quality controller at a well-known apparel manufacturer in Colombo, Sri Lanka. I joined the sector right after completing my A-Level examinations as my family was facing financial hardships. Over time, I started speaking about the problems faced by workers from within the workers’ committee established in the factory – there wasn’t a union there. This resulted in my dismissal.

As I felt it was unfair, I filed a case against the factory. I studied the law, learned about my rights, and decided to represent myself in court… and I won!

When I received compensation, it instilled in me the belief that we can win—if we fight, we can secure our rights. As a garment sector worker, I kept intervening in issues faced by workers. That is what led to the start of Stand Up Movement Lanka.

‘The factories fear our intervention’

When we receive reports of unfair labour practices or dismissals, we work to ensure justice. However, there is a palpable sense of fear. For example, a worker faced reprisals at her workplace for visiting our office in her uniform. That’s when we realized the factories were closely monitoring our office. Whenever a worker visits us in uniform, the factory management finds out about it by the next day. They fear our intervention.

We work on issues relating to protection and promotion of workers’ rights. A worker in the garment sector sacrifices their life pursuing someone else’s targets, while merely dreaming of their own.

Wages are often dependent on the completion of tight targets which means that on the factory floor, team workers often become worried if anyone takes a break or slows down, even if it is to simply go to the restroom. This has led to a harmful competition that creates undue animosity among workers, as they work under pressure day in and day out. All so that they can meet company targets in a short time frame and afford their next meal. Their happiness, sadness, children’s education, and nutritional needs are all dependent on their wages.

In Sri Lanka’s Free Trade Zones, the workforce predominantly consists of young, unmarried women who have migrated from remote and underprivileged villages, living temporarily in these areas. There are also those from the LGBTQI community working within these zones. The wage scales for workers are determined by their gender. The majority of workers at the lower levels, such as machine operators, are women and their salaries are low. In positions that offer higher salaries, such as those above supervisor level, it is rare to see a woman.

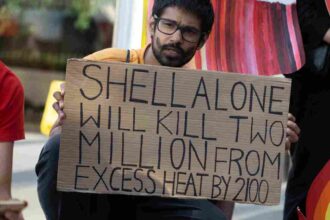

There have been efforts to exploit these workers under the guise of providing flexibile working arrangements. This has led to an increasing informalization of the sector and reduction in working hours while still expecting workers to meet their targets. They are also seeing their various benefits cut, wages reduced and are being pushed deeper into poverty. This unfortunate situation is not endemic to Sri Lanka’s garment sector alone but is rooted in global issues.

‘The fight for workers’ rights is a regional struggle’

We often work closely with similar regional civil society organizations and trade unions and have noticed that garment workers are often exploited in a similar manner everywhere. Therefore, we believe our struggle to improve the lives of workers must be carried out at a regional level, and we must fight together for it.

The governments must bear the responsibility to formulate basic principles to uplift the lives of the garment workers. Instead, they disregard workers’ needs and focus on investors when formulating their policies and legal frameworks. This signals to the factories that exploitative practices are acceptable as long as they bring investments into the country.

Global fashion brands too have a greater responsibility to ensure they are not linked to any abuses. To do so, the brands should take the initiative to ensure workers make a living wage or that gender rights are protected on the factory floors with which they do business, even if indirectly. To follow through on their commitment to human rights, these brands have to look into where they are sourcing labour from and say ‘NO’ to countries that do not enable trade unions and uphold labour rights until these changes take place. This is level of engagement can truly make a difference in our lives.

We often notice that people seem to feel good when they wear fashionable clothes, but behind that satisfaction lies the sacrifice, blood, sweat, and tears of countless workers, which is frequently forgotten. I urge everyone to reflect on this when they wear clothes and ask themselves if they know where and how their clothes are made, and whether they can truly feel happy about wearing them.

We need solidarity for this change to happen. If we join hands, together we can win this struggle for the rights of garment workers — sign our petition now.

https://youtu.be/eq_DLpQWPIM